Introduction

In this article, we are going to talk about using the nvarchar data type. We will explore how SQL Server stores this data type on the disk and how it is processed in the RAM. We will also examine how the size of nvarchar may affect performance.

Actual data size: nchar vs nvarchar

We use nvarchar when the size of column data entries are probably going to vary considerably. The storage size (in bytes) is twice as much the actual length of data entered + 2 bytes. This allows us to save disk storage in comparison of using nchar data type. Let us consider following example. We are creating two tables. One table contains nvarchar column, another table contains nchar columns. The size of the column is 2000 characters (4000 bytes).

CREATE TABLE dbo.testnvarchar (

col1 NVARCHAR(2000) NULL

);

GO

INSERT INTO dbo.testnvarchar (col1)

SELECT

REPLICATE('&', 10)

GO

CREATE TABLE dbo.testnchar (

col1 NCHAR(2000) NULL

);

GO

INSERT INTO dbo.testnchar (col1)

SELECT

REPLICATE('&', 10)

GO

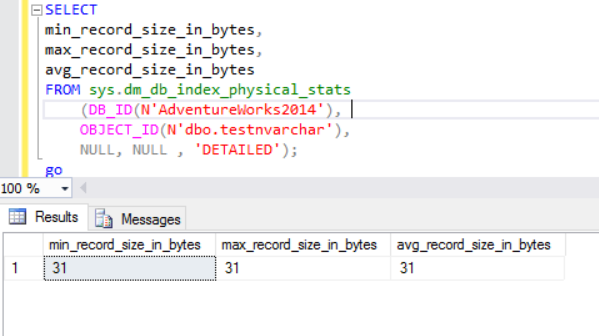

The actual row size is:

As we can see, the actual row size of the nvarchar datatype is much smaller than the nchar datatype. In the case of the nchar datatype, we use ~4000 bytes to store 10 symbols character string. We use ~20 bytes to store the same character string in case of the nvarchar datatype.

The SQL Server engine processes data into RAM (buffer pool). What about row size in the memory?

Actual data size: HDD vs RAM

Let’s execute the following query:

SELECT col1 FROM dbo.testnchar;

There is no difference between disk and RAM utilization in case of the fixed-length character string.

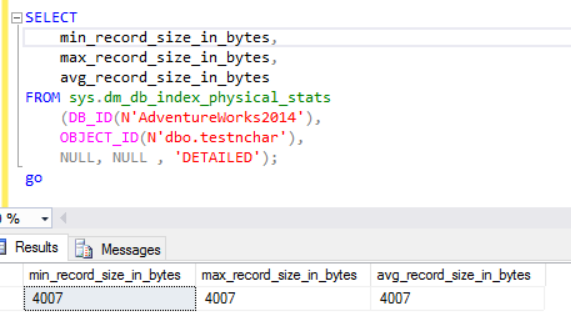

SELECT col1 FROM dbo.testnvarchar;

We can see that the SQL Server Engine requested the memory for only the half of declared row size (2000 bytes instead of actual 20 bytes) and several bytes for an additional information. From one side we decrease disk space usage but from another we can inflate the requested RAM. This is a side effect of the using of the varying character datatypes. This side effect can heavy impact on the resources in some cases.

FORMAT(): RAM requested vs RAM utilized

We use the FORMAT function, which returns a formatted value with the specified format and optional culture. The return value is nvarchar or null. The length of the return value is determined by the format. FORMAT(getdate(), ‘yyyyMMdd’,’en-US’) will result in ‘20170412’. We need 16 bytes to store this result on the column on the disc (the result will be nvarchar(8)). What is the data size in the RAM for the particular data?

Let’s execute the following query. We use the following environment:

- AdventureWorks2014

- MS SQL 2016 development edition

- dbo.Customer (19’820’000 records) contains data from Sales.Customer (19’820 records have been uploaded 1000 times)):

;WITH rs

AS

(SELECT

c.customerid

,c.modifieddate

,p.LastName

FROM [dbo].[Customer] c

LEFT OUTER JOIN [person].[person] p

ON p.BusinessEntityID = c.PersonID)

SELECT

customerid

,LastName

,FORMAT([modifieddate], 'yyyyMMdd', 'en-US') AS md

,' ' AS code INTO #tmp

FROM rs

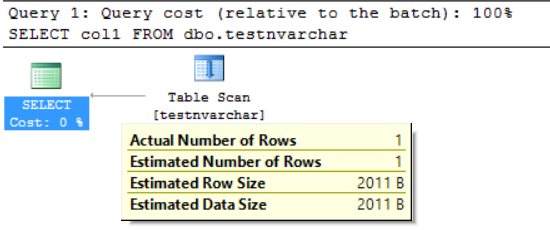

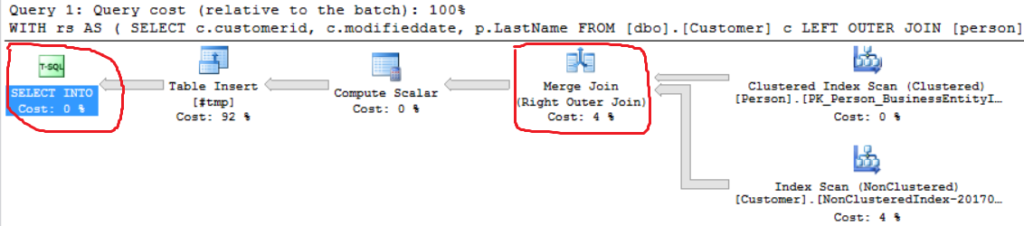

The Query execution plan is quite simple:

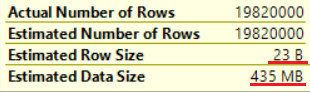

The first operation is “Clustered index scan” on dbo.Customer table. ~19 000 000 records have been read. Estimated Data Size is 435 Mb.

The next operation is “Compute Scalar” (calculation of the FORMAT() function). The result is quite unexpected as we format 16 bytes character string. The row size increased dramatically from 23 bytes to 4019 bytes. The same with the Estimated Data Size — from 435 MB to 74 GB. We can see that FORMAT() returns NVARCHAR(4000).

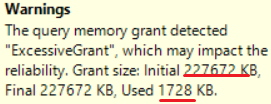

MS SQL Server 2016 has the great ability to show excessive memory grant. We can see the warning in the last operation (T-SQL SELECT INTO):

This is “over granted” of the memory: more than 90% of the granted memory is not used.

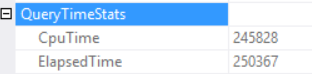

The query time statistics are:

The long execution time depends on a non-effective scalar function execution and back side effect of an Excessive Memory Grant – Hash Match (Right Outer Join). We have got a cumulative effect of two different causes: multiple scalar function execution and excessive memory granting.

The SQL Server engine can grant no more than 25% of the allowed memory per query. We can change this amount in the enterprise edition of the MS SQL Server using the resource governor. The granted memory consists of two parts: required and additional. A required memory is used for the internal needs – for sorting and hash join operations. Additional memory is based on the Estimated Data Size. If both required and additional memory exceeds the limit of 25%, SQL Server engine grants another 25% of the available memory. Read the SQL Server memory grant post for details.

Let’s execute the same query without the FORMAT() function.

;WITH rs

AS

(SELECT

c.customerid

,c.modifieddate

,p.LastName

FROM [dbo].[Customer] c

LEFT OUTER JOIN [person].[person] p

ON p.BusinessEntityID = c.PersonID)

SELECT

customerid

,LastName

,' ' AS code INTO #tmp

FROM rs

We can see another Right Outer Join implementation (Merge Join instead of Hash Join).

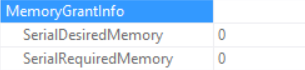

Memory Grant info is (if no Sorting and the Hash Join SQL Server can grant no memory):

The query time Statistics are (time is decreased predictably: no scalar function execution, the Estimated Data Size is smaller than in the previous sample):

So we are inflating the “granted memory” up to 222 MB (and are using less than 2 MB of it) by using the FORMAT() function. The data volume in the example is small.

Long time execution query

Consider the real SQL query from a production environment. This query has been executed during a batch loading process (not a classical transactional scenario). We use MS SQL Server started on Amazon Web Services (AWS, Amazon Relational Database Service). DB instance characteristics are 160 GB of RAM (not more than ~30 GB of the RAM can be granted per query) and 40 vCPU. The SQL query was almost the same as the example above (the difference is in amount of tables and data size): CTE included join between 6 tables. The “Master table” (a table in the FROM clause) contains ~175’000’000 records and the data size is 20GB. The Lookup tables (right table in the JOIN clause) are small (in comparison with the main table). The SQL query contains two calls of the FORMAT() function (two columns from the “master table” table are the parameter of this function).

Production query looks like this:

;WITH rs AS ( SELECT <in column list>, c.modifieddate, c.createddate FROM [Master table] c LEFT OUTER JOIN [table1 ] p1 ON … LEFT OUTER JOIN [table2 ] p2 ON … LEFT OUTER JOIN [table3 ] p3 ON … LEFT OUTER JOIN [table4 ] p4 ON … LEFT OUTER JOIN [table5 ] p5 ON … ) SELECT DISTINT <out column list>, FORMAT([modifieddate], 'yyyyMMdd','en-US') AS md, FORMAT([createddate], 'yyyyMMdd','en-US') AS cd INTO #tmp FROM rs

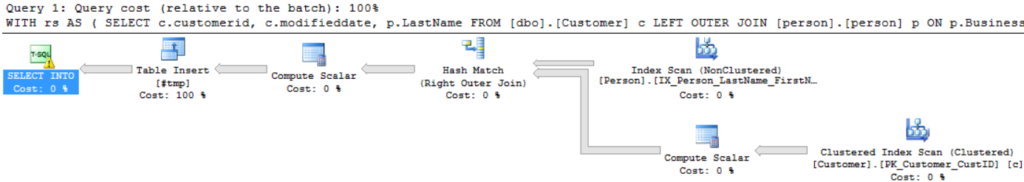

The “picture” of the execution plan is below (the execution plan is simple: sequential joins and sort (DISTINCT key words) on the top):

Let us explore the information in detail.

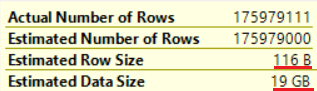

The first operation is “Table scan” (all is correct, no surprises):

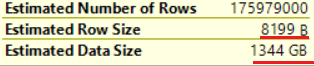

The “Scalar compute” operation increases dramatically the Estimated Row Size as well as the Estimated Row Size (from 19 GB up to 1,3 TB). Two calls of the FORMAT() function added about 8000 bytes to the Estimated Row Size (but the actual data size is smaller).

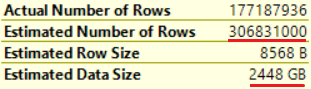

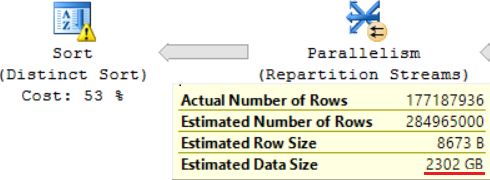

One of the JOIN operation (Hash Match, Right Outer Join) uses non-unique columns from the right table. It does not matter in the case of a few records. This is not our case. As a result Estimated Data Size are increasing up to ~2,4TB.

There is a warning also (no enough RAM to process this operation):

The SQL query contains a “Distinct Sort” operation on the top, which looks like the cherry on the top of a cake. We can see the same warning there.

A result of using a scalar function is a long time for query execution: 24 hours. One of the causes of this issue is an incorrect estimation of the requested data size based on “Estimated Data Size”. Without using the FORMAT() function, MS SQL Server executes this query in 2 hours.

Conclusion

Developers should be careful when using nvarchar and varchar data types. Selecting redundant data types for columns may lead to inflating of the required memory. As a result, RAM will be wasted, database performance will be degraded.

Tags: sql server, t-sql Last modified: September 23, 2021